In Partnership with CSL Behring

In recent decades, huge strides have occurred in every aspect of transplant, from surgical techniques to immunosuppressive drugs. However, as demand for organs rises, organ supply has not increased to match this demand. This problem has fueled an innovation explosion in many fields like policy, bioengineering, and computer science; extraordinary scientific ideas are under way for addressing issues from the waitlist to all the way through improving post-transplant kidney function. Three notable approaches include: increasing the donor kidney supply, decreasing demand for organs, and increasing donated kidney duration.

In part 3 of this innovation series, we will focus on preserving donated kidneys:

Donated kidneys can last a long time, especially with lifestyle changes and compliance with the immunosuppressive drugs. Deceased donor kidneys last on average 8-12 years, and living donor kidneys can last on average 12-20 years. If you would like to learn more about complications or rejection after transplant, see the TransplantLyfe article here. However, there may be transplant complications, or the donated kidney reaches the end of its lifespan, resulting in the need for a second transplant. Some estimate that almost 30% of patients on the transplant waiting list are waiting for a second transplant[1]. Thus, innovations in preserving donated kidney function are crucial, especially as demand for first kidney transplants rise.

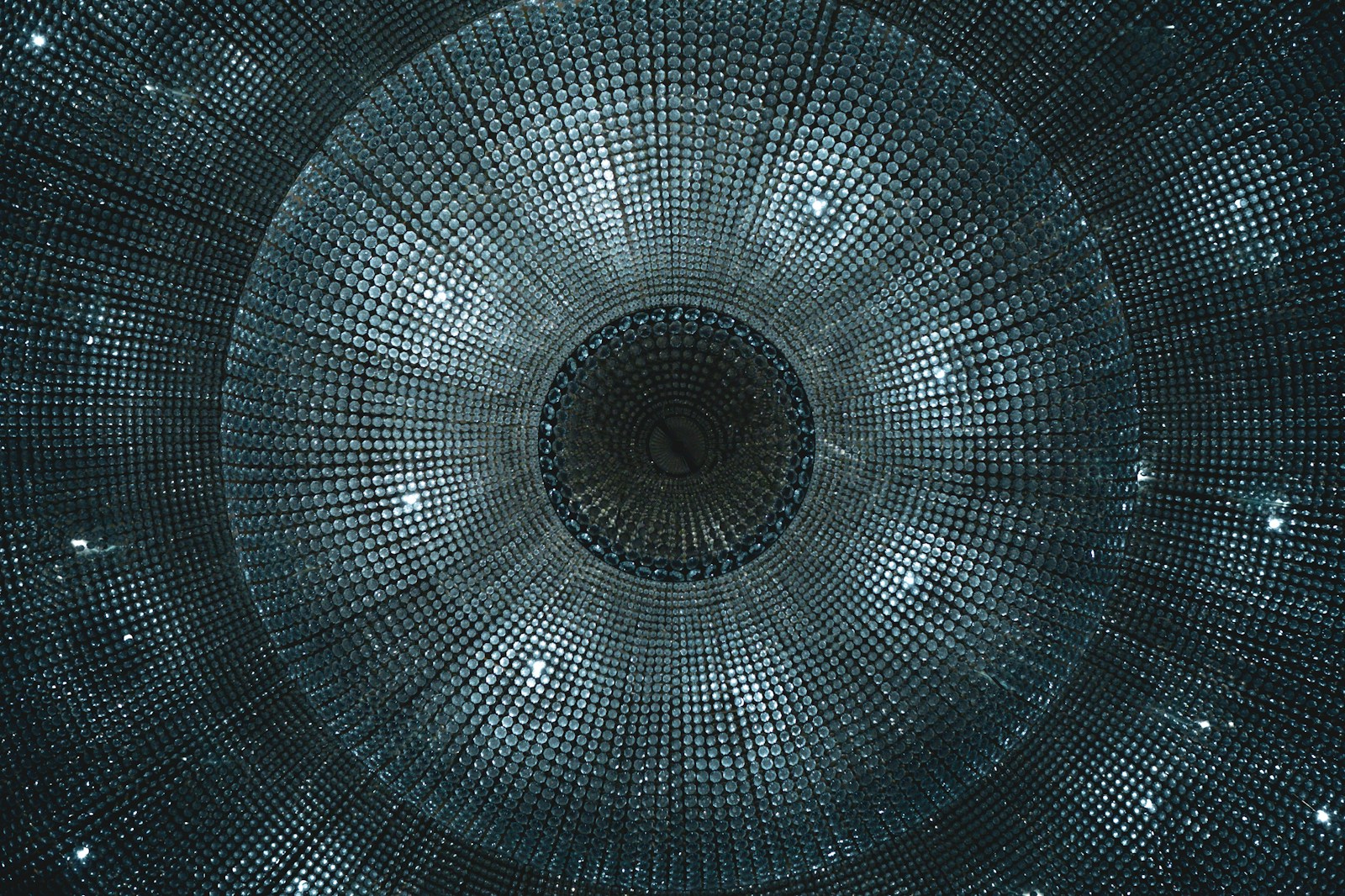

The first step, better matching donor and recipient to ensure the best compatibility, is underway. This helps prevent rejection and other complications from the donor’s immune system. Sometimes, patients are not given kidneys that are optimal matches, due to lack of availability, geography, or timing. A transplant team at John Hopkins has developed a machine to continuously pump blood through a donor organ, increasing its endurance and transplant viability[2]. Improved computer matching and advances in treating ESRD also ensure patients’ ability to receive an optimal kidney[3].

The next avenue of major innovation in preserving transplanted kidney function is in immunosuppression. After receiving a kidney transplant, a strict immunosuppressive regimen of drugs is used to prevent the patient’s immune system from attacking the donor kidney. However, there is a delicate balance between prescribing these drugs to prevent the immune system from being too strong and harming the new kidney, and ensuring that the patient isn’t vulnerable to the outside world without an immune system to protect them from infections. Furthermore, these drugs have a wide range of side effects, which can negatively affect quality of life, or even cause patients to cease medication compliance. Ideally, advances in research will lead to therapeutic interventions which would have minimal side effects, and only suppress the parts of the immune system that would attack the donated kidney, leaving the rest of the immune system free to function normally. As our understanding of the immune system improves, researchers and drug companies are discovering new therapeutic avenues for drug development, and are working to reduce side effects and improve targeted immunosuppression[4]. Furthermore, as clinicians and transplant specialists gain more experience with transplant recipients, there will be innovations in treating kidney transplant recipients, whether in designing a personalized drug regimen based on how the patient is matched or mismatched with the donor or in recognizing and treating complications earlier.

Conclusion:

As demand for organs rises, researchers, clinicians, policymakers, and companies are developing different innovations to improve transplantation and the experience of transplant recipients. There are many grand ideas, from 3D printing organs (see part 1 of this series to learn more) to creating wearable dialysis machines (see part 2 of this series to learn more), as well as small, practical changes that are already implemented and are impacting the transplantation field. As the mystery of transplantation is further unraveled, extraordinary scientific ideas from diverse fields like tissue engineering and computer science are being applied. The future of transplantation, even the near future, may look very different than it does today.

[1] Wong G, Chua S, Chadban SJ, Clayton P, Pilmore H, Hughes PD, Ferrari P, Lim WH. Waiting time between failure of first graft and second kidney transplant and graft and patient survival. Transplantation. 2016 Aug 1;100(8):1767-75.

[2] Markmann JF, Abouljoud MS, Ghobrial RM, Bhati CS, Pelletier SJ, Lu AD, Ottmann S, Klair T, Eymard C, Roll GR, Magliocca J. Impact of portable normothermic blood-based machine perfusion on outcomes of liver transplant: the OCS Liver PROTECT randomized clinical trial. JAMA surgery. 2022 Mar 1;157(3):189-98.

[3] Kaplan I, Houp JA, Leffell MS, Hart JM, Zachary AA. A computer match program for paired and unconventional kidney exchanges. American Journal of Transplantation. 2005 Sep;5(9):2306-8.

[4] Salvadori M, Tsalouchos A. Innovative immunosuppression in kidney transplantation: A challenge for unmet needs. World Journal of Transplantation. 2022 Mar 18;12(3):27.